Why employees switch off

A deceptively empowering topic

There’s so much going on inside this story. And we want you to come away with as full and understanding as we can give you, because it’s likely to give you an unprecedented amount of leverage.

We first identified the existence of Detached Observer Triggers back in 1995. It took us over a decade to work out all the pieces of the puzzle you’ll find below. Frustratingly, because we were so unwell, we had to get ourselves properly better so we could share them properly. And that took another 15 years. But we’re there now, and we want you to have these insights so you can take informed decisions about how you can establish a mandate to take your career to a new level.

Employee disengagement

People have long talked of the importance of Employee Engagement. But most people seem oblivious to the fact that many internal communications actively disengage employees.

This happens not so much because of the content but thanks to the way that content is expressed. So we’ll start with a quick overview, and then dive into the extraordinary world of Detached Observer Triggers.

We’ll look at:

- Nine disengagement triggers. (1 min read)

- The triggers that switch employees off unconsciously. (1 min)

- The mechanism behind the unconscious triggers. (3 mins)

- Why they only affect internal comms. (3 mins)

- The business impact they can have. (2 mins)

Nine disengagement triggers

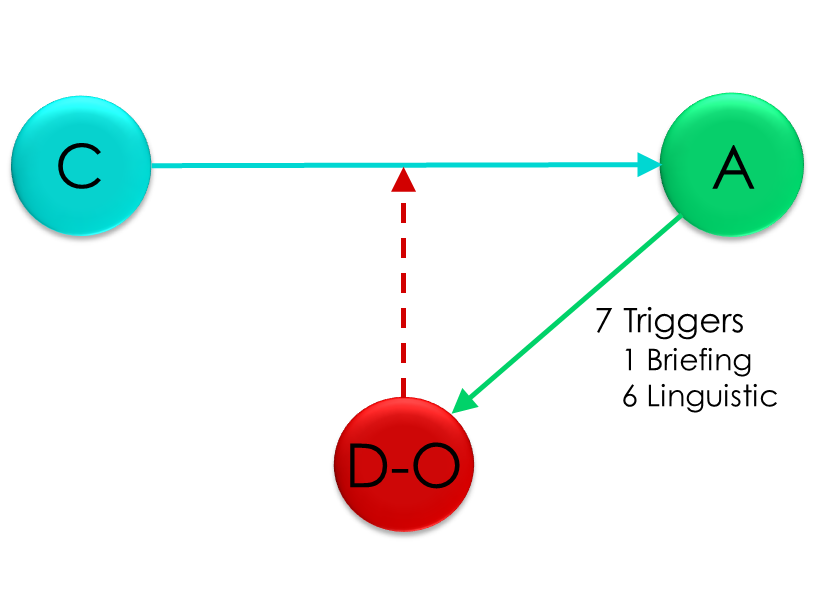

The Unconscious Triggers

One of these seven triggers comes from the communication trying to talk to more than one audience. Any time the subject matter is directed at just one of those audiences, people in the other audience(s) have no option but to switch off. Naturally, this is something your IC briefing process needs to tackle.

The other six triggers are linguistic. That is to say there are six such triggers in the English language. Other languages may have fewer or more, because the English triggers arise from different ways of using ‘You’, ‘I’ and ‘We’.

The mechanism behind the unconscious triggers

When reading anything, you can do so from any one of three different perspectives or ‘positions’. None of these is right or wrong, in an absolute sense.

But each can affect how you respond to the words in front of you.

The Communicator position

People often adopt this position when, say, filling in an employee survey, which might include something phrased along the following lines:

‘I believe this company cares about its people’

Because this statement written in the first person (‘I’) its phraseology is designed to make you feel it is you who’s written the very words you’re reading: in short, that you are the communicator. “These words are ‘coming from’ me.”

And it’s OK in a survey, because the people who created it want its recipients to communicate their answers back to them. (But in other contexts it can go horribly wrong.)

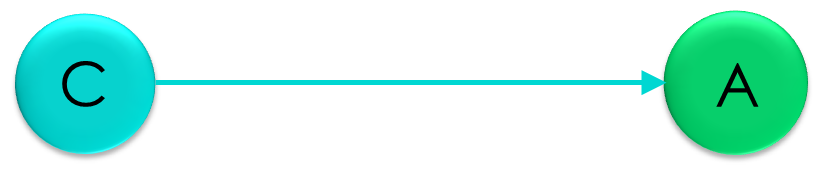

The Audience position

In this position, you do not feel that you have written the words, but that someone else has done so, and that those words are being said to you. Inevitably, then, this is the position employees need to be in if they’re going to be taking or avoiding actions as a result of having read an internal communication.

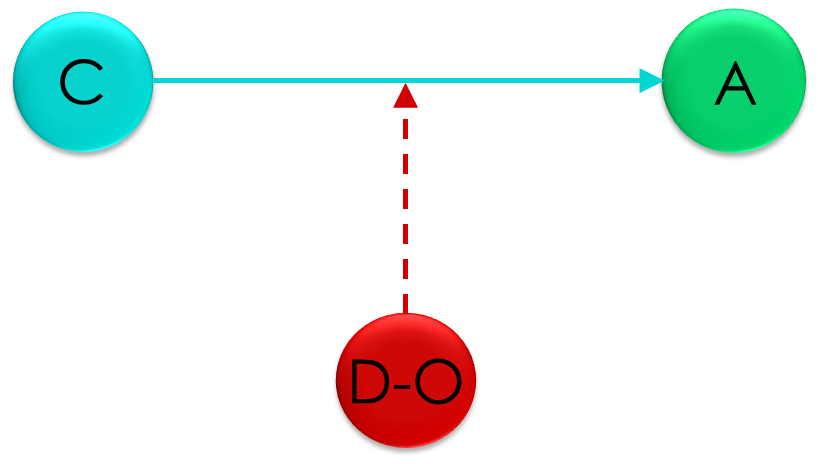

The Detached Observer position

This is the position employees tend unconsciously to step into when, for example, they’re on a ‘copies’ list for an e-mail. It’s a fly-on-the-wall position, which, when you adopt it yourself, will make you feel as if you’re eavesdropping on a conversation between a communicator and an audience to which you don’t belong.

The words are not being said by you, nor to you. “These words are coming from someone else and speaking to another someone else (or to a group of others).”

Implications

So, think on this for a moment. Let’s just imagine you’re on the copies list of an email, which says: ‘We need to discuss this further, so please message me to set up a meeting’. If you’re on the copies list, are you being asked to message the sender? No. That instruction was being aimed at those on the distribution list.

Of course, you might decide you want to be involved, but you weren’t being directly told to take that action. So – and this is the critical point – people in the Detached Observer Position tend not to do any actions mentioned in the communications before them (assuming they’re even paying attention at all by that point). And whatever the communication’s intended outcome, those Detached Observers won’t be delivering it.

So this is a really big deal as far as internal communication is concerned because the seven unconscious ‘Detached Observer Triggers’ can push people out of the audience position, and turn them into Detached Observers. in short, these triggers make internal communications fail with some or all of their audiences. And they’ll do so without those employees knowing why it’s happened – or, oftentimes, even that it’s happened (which, crucially, means they’re not going to tell you).

Why internal communications are uniquely vulnerable

These triggers bypass recreational communications altogether (books, newspapers, theatre plays, TV shows etc). And they have little if any impact on external business communications. How come?

Recreational communications

It’s probably easiest to explain this with a little thought experiment. Let’s imagine you’ve had to hire a car. When you turn on the ignition, the radio bursts into life. It’s playing an old song by the Beatles. And because it’s a catchy tune, you decide to listen to it, as they belt out these lyrics:

“If there’s anything that you want. If there’s anything I can do, just call on me, and I’ll send it along, with love, from me, to you…”

Now, think for a moment: who specifically do you imagine the ‘you’ is, to whom Lennon and McCartney are addressing those sentiments? Are those words being sung to you, or to someone else? Obviously they’re addressed to someone else – as are the lyrics of any other songs you might hear.

So here’s the thing: when you’re on the receiving end of recreational communications, you tend to start out in the Detached Observer Position. In fact, in TV and films there’s a specific term for treating the audience as anything other than a detached observer. It’s called ‘Breaking the fourth wall’.

It’s a similar story with books – which is why it was so memorable when Charlotte Bronte broke the fourth wall at the beginning of the last chapter of Jane Eyre, with the line:

‘Reader, I married him’.

And it all explains why the linguistic triggers have no impact on recreational communications. You can’t be pushed into the Detached Observer Position if you’re already there from the start.

But that’s not the case with business communications. So why would PR or Marcoms be immune to these triggers?

External business comms

Although external communications can contain these triggers, they rarely make any difference, for two reasons.

Imagine you’re watching a TV show, and an ad break comes on. And imagine you’ve chosen to sit through it (rather than channel hop, or nip out to the kitchen). Now suppose there’s an ad for a product you’re not interested in. Chances are you would become a detached observer, thinking: “This isn’t talking to me.” (because you’re not in the market for disposable nappies, or chair lifts, or artisan chutney, or whatever.)

But the fact that you’ve become a detached observer doesn’t matter. Why not?

- The communicator never wanted to talk to you in the first place. They’re interested only in people who are in the market for what they’re selling.

- Although they’ve had to pay for the air time, they don’t have to pay you for yours.

So, with a marketing communication, it’s always OK if at least some people who receive it switch off. (Obviously the companies want to place their ads where they’ll reach the maximum number of potential customers, but they’ll always end up in front of many people to whom they’re not relevant.)

But there are different dynamics playing out when it’s an internal communication.

The financial dynamic

The employer has to pay the audience for their time. So wasting employees’ time, with messages that aren’t relevant to them, is costing money (probably lots of it).

It may sometimes be OK (even inevitable) that some employees switch off occasionally. (A notice about new car parking arrangements won’t matter to folk who walk to work, or get the train.)

But unlike external comms, the cost of employee time means this cannot be the default. And for moral or even legal reasons there are times when it’s absolutely not OK to lose a single person from your audience (eg Health & Safety).

The emotional dynamic

Losing internal audiences is actually more likely. Remember, you would have sat through that ad break because you chose to do so. Marketing audiences volunteer themselves to be there. Internal audiences often watch or read communications because they feel they have to. And internal communications come with another complication.

The relationship dynamic

With external comms it’s relatively simple to keep the relationship clear between communicator and audience. In effect it goes like this:

‘We’ (the organisation) are talking to ‘you’ (the customer) about ‘this’ (the proposition).

But with internal comms that relationship can easily get more tangled – especially when you have situations where it’s effectively:

‘We’ (the organisation) are talking to ‘you’ (the organisation) about ‘us’ (the organisation).

For all these reasons, internal audiences are far more likely to switch off than external ones, and have the potential to do loads more damage when that happens. And the real kicker is they won’t even know they weren’t supposed to.

The consequences

There are two ways of thinking about this. Firstly, how many employees is each trigger likely to lose? And second, how much harm could it do?

How many employees could you lose?

This isn’t a simple question to answer. For reasons we’ve never understood, some people seem to have a sort of immunity to certain triggers. And this appears to be pretty random.

Another wrinkle is the fact that even though each trigger has a discrete linguistic structure, its potency can be affected by the structure of the sentence in which it appears. Having said that, in our experience every trigger ends up losing at least some people.

And in certain contexts some triggers (particularly the first person plural) are pretty much guaranteed to lose everyone. The key point, though, is that these are risks you simply don’t need to run. But what impact can they have if you do?

Four significant downsides

These triggers deliver nothing but bad news:

- Employee experience inevitably suffers when people feel they’re not being communicated with. And even though they are receiving communications, that’s not how it feels to them.

- Mistakes, often costly ones, could be happening. And the cost may be more than just financial: there are potential legal ramifications (health & safety implications, for example – which could be enormous). There’s also potential damage to both employer and consumer brand value.

- Failed internal communications are having to be repeated, adding to the communication costs and overload – and potentially exacerbating employee frustration and stress.

- These triggers, and the mechanism which lies behind them, can seriously mess with the approvals process too – making it longer and more tortuous than it needs to be.

Under the skin of the Approvals Process

Think about this: which position will someone adopt when approving a communication? The truth is, no one knows. So what’s likely to happen if:

- one of those approvers is unconsciously in the Communicator position,

- someone else is reading it as a member of the Audience, and

- a third is doing so as a Detached Observer?

What are the chances they’ll all have the same gut reactions to the words in front of them? Interesting, huh?

And ‘positioning’ is just one of five different unconscious processes people can do differently when approving communications. (This is a whole other discussion in itself.)

Managing the triggers makes everyone’s lives better

Clearly the implications of these triggers are far reaching, in terms of their potential to adversely affect:

- employee well-being

- operating costs – with the number of mistakes and misunderstandings they can cause, and amount of time and money it can take to put them right

- consumer and employer brand reputation and value

- legal liabilities.

The good news is that the sheer number and scale of these downsides could give you exactly the leverage you need to change the status quo – for everyone’s benefit. In financial terms alone, depending on the size of your organisation, removing these triggers could easily be worth millions or even tens of millions of dollars a year. (And you can measure this.)

They can hold the key to ending all manner of challenges you may have had, when trying to get people to:

- follow language standards,

- set aside enough time to brief you properly

- not mess with copy you’ve written when they’re approving and signing it off.

Understanding these triggers can help you and your team establish an unprecedented level of confidence and authority – and take a quantum leap in terms of your value-add.